Firebreak Sprints: When Your Entire Engineering Team Needs to Stop and Fix the Foundation

Monday morning, 9:15 AM. Your security engineer posts in Slack: “SonarQube scan results from the weekend: 347 critical vulnerabilities, 892 high-severity issues across the codebase. Most are dependency vulnerabilities that need immediate patching. This blocks our SOC2 audit next month.”

Monday morning, 9:47 AM. Your platform lead escalates: “We just discovered a threading bug in the connection pool library we use across 23 microservices. It’s causing intermittent crashes in production. Every service using this library needs to be patched and redeployed.”

Monday morning, 10:23 AM. Your VP Engineering shares DORA metrics from last quarter: “Deployment frequency dropped from 12 per week to 3 per week. Change failure rate increased from 4% to 18%. Mean time to recovery went from 45 minutes to 6 hours. Our delivery performance is degrading fast.”

Three different crises. One common reality: Your team needs to stop building new features and fix the foundation.

Not “find time between feature work.” Not “address this gradually over the next six months.” Stop. Focus. Fix the foundation before it collapses under the weight of technical debt, security vulnerabilities, or platform reliability issues that make every future feature take longer to ship.

This is when you call a firebreak sprint—a focused period where your entire engineering organization aligns around a single platform health objective, pausing feature work to address critical technical issues that can’t wait.

Most product organizations resist firebreak sprints because they’re terrified of telling stakeholders “we’re not shipping features for two weeks.” But the alternative—accumulating technical debt until velocity collapses entirely—is far worse. Let’s explore how to call firebreaks strategically, communicate them effectively, and use RoadmapOne to insert them without destroying stakeholder trust.

What Are Firebreak Sprints?

Firebreak sprints are dedicated periods where all engineering squads align to a single platform health or technical excellence objective, pausing feature delivery work to fix foundational problems that affect the entire system.

The term “firebreak” comes from controlled burns in forest management—intentionally burning sections of forest in controlled conditions to prevent catastrophic wildfires later. Similarly, firebreak sprints are intentional pauses that prevent catastrophic technical failures, security breaches, or velocity collapse.

The key characteristics that distinguish firebreaks from regular technical debt work are total organizational alignment (all squads work on related platform health objectives, not scattered across different feature work), time-boxed intensity (typically one to two sprints of focused effort, not ongoing background work), clear success criteria (specific measurable outcomes like “zero critical security issues” or “deploy frequency >2/day”), and explicit stakeholder communication (leadership knows features are paused and why).

Firebreaks are not normal technical debt allocation where each squad dedicates 15-20% of capacity to tech debt every sprint. That ongoing allocation is important for maintenance, but firebreaks address acute crises or systemic degradation that 15-20% ongoing allocation can’t resolve.

They’re also not unplanned emergency responses. While the trigger might be a crisis (security vulnerability discovered, production incident revealing systemic issues), the firebreak itself is a planned, coordinated organizational response rather than teams scrambling reactively.

The typical firebreak duration is one to two sprints—long enough to make meaningful progress on complex system-wide problems, short enough to be tolerable for stakeholder expectations about feature delivery pausing.

When to Call a Firebreak Sprint

Firebreak sprints are appropriate when technical health issues reach critical mass where ongoing accumulation creates more risk than the cost of pausing feature work. Here are the most common scenarios.

Scenario 1: Security or License Compliance Crisis

Security vulnerabilities and license compliance issues create legal, financial, and reputational risks that often justify immediate firebreak responses.

SonarQube or Snyk scans reveal hundreds of critical or high-severity security vulnerabilities across the codebase, often from outdated dependencies with known exploits. Each vulnerability represents a potential breach vector. Addressing them gradually over months leaves the organization exposed to exploits for the entire period. A firebreak sprint dedicated to “Eliminate all Critical/High severity security issues” allows focused effort to patch dependencies, update vulnerable code, and verify fixes across all services.

Dependency audits discover license compliance problems where the codebase uses libraries with incompatible licenses (GPL libraries in proprietary software, for example) or dependencies with licenses that violate customer contracts or regulatory requirements. These issues can block customer contracts, prevent certifications, or create legal liability. A firebreak sprint focused on “Replace all incompatible-license dependencies” resolves the compliance issue before it blocks revenue or creates legal exposure.

Pre-audit discoveries before SOC2, ISO27001, PCI DSS, or industry-specific compliance audits often reveal gaps that must be addressed before auditors arrive. A failed audit delays certifications that block customer contracts. A firebreak sprint focused on “Pass SOC2 readiness assessment with zero critical findings” ensures you’re actually ready before paying auditors to verify.

The firebreak objective is specific and measurable: “Zero critical/high vulnerabilities reported by SonarQube” or “100% of dependencies compliant with approved licenses” or “All SOC2 control requirements implemented and testable.”

Scenario 2: DORA Metrics Degradation

DORA (DevOps Research and Assessment) metrics track software delivery performance across four key dimensions: Deployment Frequency, Lead Time for Changes, Change Failure Rate, and Mean Time to Recovery. When these metrics degrade significantly, it signals systemic platform health problems that compound over time.

Deployment frequency dropping from healthy cadence (10+ deployments per week) to concerning levels (2-3 per week) often indicates deployment pipeline problems, environmental instability, or fear of deploying due to past failures. Teams delay deploys to batch changes, reducing feedback loops and increasing risk per deploy. A firebreak sprint focused on “Improve deployment pipeline to enable 2+ deploys per day with <5% failure rate” addresses the systemic issues preventing frequent, confident deploys.

Change failure rate increasing from acceptable levels (<5%) to concerning levels (15%+) means a growing percentage of deployments cause production incidents, rollbacks, or hotfixes. This indicates inadequate testing, insufficient staging environments, or architectural fragility where changes in one area break unrelated functionality. A firebreak sprint on “Reduce change failure rate to <5% through improved testing automation and deployment safety” addresses root causes rather than just fixing individual failures.

Mean time to recovery growing from minutes to hours means when things break, teams struggle to diagnose and fix issues quickly. This suggests inadequate observability, poor deployment rollback mechanisms, or architectural complexity that makes troubleshooting difficult. A firebreak sprint focused on “Reduce MTTR to <30 minutes through improved observability and automated rollback” gives teams the tooling to recover quickly when failures occur.

Lead time increasing from hours to days or weeks means the time from committing code to deploying to production is growing, reducing team velocity and making it harder to respond to customer needs or competitive pressure. A firebreak sprint on “Reduce lead time to <4 hours through pipeline optimization and automated testing” removes bottlenecks that slow the feedback loop.

The firebreak objective is anchored in specific DORA metric targets: “Achieve deployment frequency >2/day, change failure rate <5%, MTTR <30min, lead time <4 hours.”

Scenario 3: Platform Reliability Crisis

Production reliability issues that affect multiple services or customer-facing functionality often justify firebreaks when they reach critical mass.

Common threading bugs or connection pool issues discovered in shared libraries used across many microservices create cascading failures across the platform. One service crashes, taking down dependent services, creating cascading outages that are hard to isolate and recover from. The bug might affect 20+ services, and patching each independently takes weeks while exposing customers to ongoing reliability issues. A firebreak sprint focused on “Fix threading bug across all 23 affected microservices and deploy updated services” coordinates the fix across all services simultaneously.

Database performance degrading under load indicates scalability problems that will only worsen as usage grows. Query times increasing from 50ms to 2 seconds creates user-facing slowness that drives churn. Addressing this piecemeal—optimizing one query this sprint, adding one index next sprint—takes too long while customers experience degraded performance. A firebreak sprint on “Optimize database performance to achieve p95 query time <200ms” focuses the team on comprehensive database optimization.

Infrastructure scaling problems where the platform can’t handle traffic spikes or steady growth patterns mean you’re one viral moment or marketing campaign away from site outages. A firebreak sprint focused on “Implement auto-scaling and load distribution to handle 5x traffic spikes without degradation” builds the infrastructure resilience needed before the crisis hits.

Memory leaks or resource exhaustion issues where services gradually consume more memory until they crash and restart, creating intermittent outages that are hard to debug. A firebreak sprint on “Eliminate memory leaks across all long-running services” uses profiling tools to find and fix resource leaks systemically.

The firebreak objective is reliability-focused: “P95 response time <200ms,” “Zero cascading failures from shared library issues,” “Platform handles 5x traffic without degradation.”

Scenario 4: Developer Experience Breakdown

When developer productivity tools become so degraded that engineering velocity suffers across the entire organization, a firebreak focused on developer experience (DX) can pay dividends.

Local development environment setup taking days instead of hours means new engineers can’t contribute quickly, and existing engineers who need to set up new projects or rebuild environments lose days to configuration battles. A firebreak sprint on “Reduce local environment setup to <30 minutes through containerization and automation” removes this massive productivity drag.

Test suite runtime growing from minutes to hours means engineers either skip running tests (reducing quality) or wait around for test results (reducing velocity). A 45-minute test suite run between commits means engineers context-switch rather than staying in flow. A firebreak sprint focused on “Reduce full test suite runtime to <8 minutes through test parallelization and optimization” restores rapid feedback loops.

Build times preventing rapid iteration where it takes 15+ minutes to build and deploy to development environment means engineers can’t iterate quickly on solutions. A firebreak sprint on “Reduce build time to <3 minutes through incremental builds and caching” removes this iteration friction.

Tooling gaps where engineers lack proper observability, debugging tools, or development utilities means diagnosing problems takes hours instead of minutes. A firebreak sprint focused on “Implement comprehensive local debugging and profiling tools” gives engineers the visibility they need to work efficiently.

The firebreak objective is DX-focused: “Environment setup <30min,” “Test suite runtime <8min,” “Build time <3min,” “All services have local debugging capability.”

Scenario 5: Because it’s great for the Product, the Individual, and the Team

I love this post from Lalit Magnati: https://lalitm.com/fixits-are-good-for-the-soul/

Once a quarter, my org with ~45 software engineers stops all regular work for a week. That means no roadmap work, no design work, no meetings or standups.

Instead, we fix the small things that have been annoying us and our users:

- an error message that’s been unclear for two years

- a weird glitch when the user scrolls and zooms at the same time

- a test which runs slower than it should, slowing down CI for everyone

The rules are simple: 1) no bug should take over 2 days and 2) all work should focus on either small end-user bugs/features or developer productivity.

The Cost of Ignoring Foundation Problems

Before diving into how to run firebreaks, it’s critical to understand why delaying them is actually more expensive than pausing feature work for 1-2 sprints.

Technical debt compounds like financial debt (and overlaps significantly with Keeping The Lights On (KTLO) work). Each sprint you delay fixing the threading bug, more services built on the vulnerable library go into production, increasing the surface area of the problem. Each sprint you delay addressing security vulnerabilities, more code touches vulnerable dependencies, making the eventual fix more complex. Each sprint you delay DORA metric degradation, more process inefficiencies calcify into “how we do things,” making them harder to change later.

The compound interest on technical debt manifests as degraded engineering velocity. When deployment takes 45 minutes instead of 5 minutes, every deploy wastes 40 minutes of engineering time. When test suites take 45 minutes instead of 8 minutes, engineers either skip tests (reducing quality) or lose hours daily to test waits. When builds take 15 minutes instead of 3 minutes, rapid iteration becomes impossible. These productivity drags affect every engineer, every day, compounding across the entire organization.

Reliability incidents increase as foundation problems accumulate. The threading bug that affects one service today affects twenty services in three months, creating cascading outages that damage customer trust and consume engineering time in firefighting rather than feature building.

Security breaches become more likely and more damaging as vulnerabilities accumulate. One critical vulnerability discovered and exploited can cause data breaches, regulatory fines, customer churn, and reputational damage that far exceeds the cost of pausing feature work for two weeks to patch systematically.

Best engineers leave when platform health degrades. Top performers want to work on interesting product problems, not constantly firefight production issues caused by foundation neglect, or struggle with 45-minute test suites and deployment pipelines that fail 20% of the time. When your best engineers leave, organizational capability degrades, making foundation problems even harder to fix.

The one-time cost of a two-sprint firebreak is dwarfed by the ongoing cost of accumulating technical debt that compounds daily across the entire engineering organization. Firebreaks are investments, not expenses.

Planning a Firebreak Sprint

Effective firebreak sprints require as much planning discipline as feature delivery work—perhaps more, because they’re asking the entire organization to align around a single objective.

Setting the Objective: Measurable and Achievable

The firebreak objective must be specific enough to guide decision-making about what work belongs in the firebreak versus what should wait, measurable enough to know when you’ve succeeded, and achievable within the firebreak timeframe (typically 1-2 sprints).

Vague objectives like “Improve platform health” or “Reduce technical debt” or “Fix quality issues” fail because they don’t provide clear success criteria. How do you know when platform health is sufficiently improved? What counts as technical debt reduction?

Specific objectives like “Eliminate all Critical and High severity security issues reported by SonarQube,” “Achieve DORA metrics of deployment frequency >2/day, change failure rate <5%, MTTR <30min,” or “Fix threading bug across all 23 affected microservices” provide clear targets.

Measurability comes from objective definitions tied to tools, metrics, or specific counts. “Zero critical issues in SonarQube dashboard.” “DORA metrics dashboard shows >2 deploys/day average.” “All 23 microservices deployed with patched library version and zero production errors for 48 hours.”

Achievability requires scoping the firebreak to what one or two sprints of focused effort can realistically accomplish. If the security scan shows 800 critical issues, maybe the firebreak objective is “Eliminate all 347 critical dependency vulnerabilities” (achievable) rather than “Fix every security issue across the entire codebase” (unrealistic for two sprints).

The team should understand why this objective matters to the business, not just to engineering—this is where Run-Grow-Transform tagging helps frame firebreaks as essential “Run” work, not discretionary improvements. “Critical security vulnerabilities block our SOC2 audit, which blocks our enterprise sales pipeline, which puts Q3 revenue at risk.” “Threading bugs cause production outages that churn customers and damage our reliability reputation.” “DORA metric degradation means every feature takes longer to ship, making us less competitive.” This business framing helps stakeholders understand why pausing feature work is justified.

Communicating to Stakeholders: The Business Case for Pausing

Announcing a firebreak sprint to stakeholders who expect continuous feature delivery requires clear communication about what’s broken, why it can’t wait, what happens if we don’t fix it, and what features will be delayed by how much.

The communication should lead with the business problem, not the technical problem. Instead of “We need to update dependencies,” explain “We have 347 critical security vulnerabilities that could lead to data breaches, failed audits that block enterprise contracts, or regulatory fines if exploited.” Instead of “Our deployment pipeline is slow,” explain “Deployment degradation has reduced our release velocity by 60%, making us unable to respond quickly to competitive threats or customer feature requests.”

Explain the compound interest problem. “Every week we delay this, the problem grows. More services depend on the vulnerable library. More technical debt accumulates. More engineering time gets wasted on slow tooling. Fixing it now in two focused sprints is cheaper than letting it compound for six months until we’re forced to fix it in crisis mode.”

Show the capacity math. “This firebreak consumes 20 squad-sprints (10 squads × 2 sprints). Delaying it means losing 3-5 squad-sprints per week to firefighting production issues, slow deployments, and inefficient tooling. We recoup the firebreak investment in 4-6 weeks through improved engineering velocity.”

Be explicit about feature impact. Don’t hide or minimize the delay. “These five features currently scheduled for Q2 will shift to Q3: [list features]. These three features will stay on schedule because they’re already in progress and wrapping up. Here’s the updated timeline showing the two-week push.” Transparency builds trust. Hidden delays discovered later destroy trust.

Present the ROI argument. “Two sprint firebreak investment prevents months of degraded velocity, reduces production incident firefighting by an estimated 60%, and enables us to deploy 3x more frequently, accelerating every future feature delivery.”

Scoping the Work: What Gets Fixed vs. What Waits

A two-sprint firebreak can’t fix everything. Scoping requires identifying the critical subset of issues that deliver the most impact and deferring less critical work to future sprints or ongoing tech debt allocation.

Use impact vs. effort prioritization. Security vulnerabilities that are critical severity and affect customer-facing services take priority over low-severity issues in internal tools. Threading bugs that cause production outages every day take priority over minor memory leaks that cause problems every six weeks. DORA metric improvements that unblock deployment frequency (immediately impactful) take priority over nice-to-have dashboard improvements (low immediate impact).

Break work across squads strategically. If the firebreak objective is security vulnerability remediation, some squads focus on dependency updates, others focus on code fixes for application-level vulnerabilities, others focus on infrastructure security hardening. Each squad takes a meaningful subset rather than all squads working on the same things in parallel (which creates coordination overhead without faster completion).

Define clear done criteria for each work item. “Dependency X updated to secure version Y, all services using X rebuilt and deployed, verified zero vulnerabilities related to X in SonarQube scan.” This prevents scope creep where “update dependency” becomes “rewrite entire module that uses dependency.”

Acknowledge what won’t be fixed in this firebreak. “This firebreak addresses critical and high-severity issues. Medium and low-severity issues remain in the backlog for ongoing tech debt allocation. We’ll reassess after this firebreak whether another firebreak is needed or if ongoing allocation suffices.”

All-Hands Kickoff: Making Everyone Understand Why

The firebreak kickoff meeting brings the entire engineering organization together (or all squads participating in the firebreak) to explain the objective, why it matters, how work is distributed, and what success looks like.

The kickoff should be led by engineering leadership (VP Engineering, CTO, or equivalent) to signal importance. If leadership doesn’t show up to kick off the firebreak, teams interpret it as “not really a priority.”

Frame the problem with data, not opinions. Show the SonarQube dashboard with 347 critical vulnerabilities. Show the DORA metrics trend over the past six months. Show production incident graphs revealing increasing frequency. Make the problem visceral and undeniable.

Explain the business impact. “These vulnerabilities block our SOC2 audit. No SOC2 means no enterprise contracts. No enterprise contracts means we miss Q3 revenue targets by $2M.” Or “DORA metric degradation means we’re deploying 70% less frequently than last year. Every feature takes longer. We’re losing competitive velocity.”

Present the objective clearly. “Our firebreak objective is: Eliminate all 347 critical vulnerabilities by end of sprint 15. Success means SonarQube dashboard shows zero critical issues. We’ll verify this with a final scan Friday of sprint 15.”

Distribute work across squads. “Squad A: dependency updates for frontend services. Squad B: dependency updates for backend services. Squad C: code-level vulnerability fixes. Squad D: infrastructure security hardening. Squad E: verification and deployment coordination. Each squad lead has the detailed work breakdown for their squad.”

Set expectations about trade-offs. “This is 100% focus on security for two sprints. No feature work. No nice-to-have improvements. No unrelated bug fixes unless they’re production-critical. Everything else waits until sprint 16.”

Create visibility into progress. “We’ll track progress daily in the #firebreak-security Slack channel. We’ll have a brief all-hands standup each morning to share blockers and coordinate dependencies. Leadership will provide daily updates to stakeholders about progress.”

The kickoff should leave engineers understanding why this matters, what they’re personally responsible for, and how the organization will track progress toward the objective.

How RoadmapOne Enables Firebreak Sprints

RoadmapOne’s roadmap planning model makes firebreak sprints practical through several specific capabilities that address the common challenges of inserting focused engineering work without manual timeline chaos.

Insert Firebreak Sprint Without Manual Date Recalculation

The most painful part of traditional firebreak planning is adjusting all subsequent sprint dates manually when you insert a firebreak sprint mid-roadmap. If you’re in sprint 12 and decide to insert a two-sprint firebreak before continuing with planned work, every sprint from 12 onward needs its dates adjusted by two sprints. In a spreadsheet or timeline tool, this means manually editing dozens or hundreds of date cells.

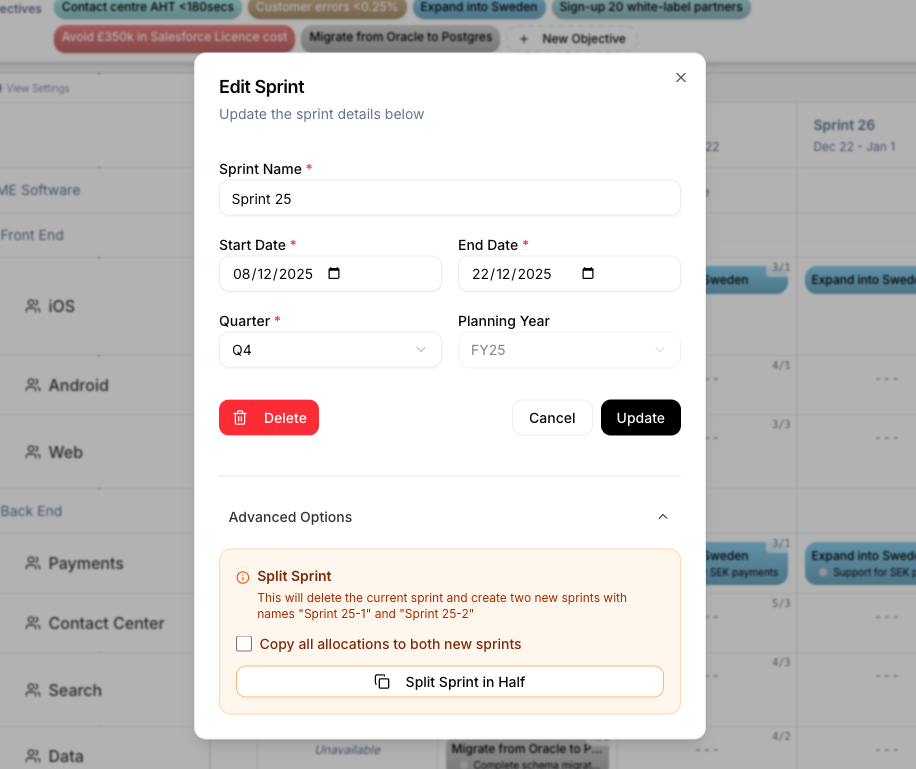

RoadmapOne’s “Insert Firebreak Sprint” function (or more generally, the insert sprint function) automatically pushes all subsequent sprints back when you insert new sprints into the calendar. You’re in sprint 12. You insert two new sprints (12a and 12b for the firebreak). The system automatically shifts what was sprint 13 to now be sprint 15, sprint 14 to be sprint 16, and so on through the rest of the calendar.

This automatic date recalculation prevents the manual spreadsheet hell of updating every sprint’s start date, end date, and quarter assignment when inserting firebreaks. More importantly, it prevents the errors that inevitably occur when manually adjusting dozens of dates—missing a cell, mistyping a date, getting quarters wrong after the shift.

The inserted firebreak sprints become regular sprints in the calendar that can be allocated to objectives like any other sprint. The key difference is that all squads will allocate to the same firebreak objective during these sprints rather than the usual pattern of different squads working on different objectives.

RoadmapOne’s insert sprint function adds new sprints to the calendar and automatically pushes all subsequent sprint dates back, preventing manual date recalculation errors when inserting firebreaks mid-roadmap.

RoadmapOne’s insert sprint function adds new sprints to the calendar and automatically pushes all subsequent sprint dates back, preventing manual date recalculation errors when inserting firebreaks mid-roadmap.

Allocate All Squads to Single Engineering Objective

During firebreak sprints, the entire engineering organization (or a substantial subset) aligns around a single platform health objective. In RoadmapOne, this means creating an engineering-focused objective (e.g., “DORA Metrics Improvement,” “Security Vulnerability Remediation,” “Threading Bug Resolution”) and allocating every participating squad to this objective during the firebreak sprint(s).

The visual impact on the roadmap grid is immediately obvious: every row shows the same objective during the firebreak sprint columns. This creates organizational alignment visibility—stakeholders can see at a glance that the entire team is focused on the firebreak objective rather than scattered across different feature work.

Creating the firebreak objective follows the same objective creation workflow as product objectives, but the content reflects platform health rather than customer-facing features. The objective name might be “Eliminate Critical Security Vulnerabilities.” The description explains the business rationale: “347 critical vulnerabilities block SOC2 audit, which blocks enterprise sales pipeline.” Key results might include “SonarQube shows zero critical issues,” “All production services updated to secure dependency versions,” “Penetration testing validates no critical vulnerabilities.”

Each squad receives an allocation to this firebreak objective during the firebreak sprint(s). The allocation might include notes about which subset of the work that squad is responsible for: “Squad A: frontend service security updates,” “Squad B: backend API security updates.” This distributes the firebreak work while maintaining the unified objective that all squads contribute to.

The capacity allocation is explicit: “3/1” developer/non-developer capacity shows that the full squad is working on the firebreak, not splitting capacity between firebreak work and feature work. This makes clear that feature work is truly paused, not just deprioritized while teams try to juggle both.

See Impact on Delivery Timelines: Transparent Feature Delays

The most important stakeholder communication challenge with firebreaks is showing exactly which features get delayed and by how much. When you insert a two-sprint firebreak starting at sprint 12, features originally scheduled for sprints 12-14 now shift to sprints 14-16 (two sprints later).

RoadmapOne makes this timeline impact immediately visible by showing the before and after allocations on the grid. Before firebreak insertion, Squad A was allocated to the retention feature in sprints 12-14. After inserting the two-sprint firebreak (which becomes sprints 12-13), Squad A’s retention feature allocation automatically shifts to sprints 14-16.

This visual timeline impact enables precise stakeholder communication. Instead of vague “some features will be delayed,” you show “the retention feature shifts from May delivery to June delivery (two sprints later). The enterprise SSO feature shifts from June to July. The mobile redesign remains on schedule because it’s already in progress and completes in sprint 11 before the firebreak begins.”

The analytics view can also show portfolio impact by comparing Q2 capacity allocation before firebreak insertion versus after. Before: 60% capacity on new features, 25% on enhancements, 15% on tech debt. After firebreak insertion: 40% capacity on new features, 20% on enhancements, 40% on platform health (the firebreak). This quantifies the trade-off stakeholders are accepting by approving the firebreak.

Stakeholders appreciate this transparency far more than discovering mid-quarter that features are delayed for “unplanned technical work.” The firebreak is planned. The delays are explicit. The trade-offs are visible.

Track Impact on Portfolio Balance: Temporary Platform Health Focus

RoadmapOne’s analytics track capacity allocation across tag categories (Run/Grow/Transform, customer journey stages, etc.), making visible how firebreak sprints temporarily shift portfolio balance toward platform health before returning to normal allocation.

Before firebreak: analytics might show 60% Grow work (new features), 30% Run work (enhancements and maintenance), 10% Transform work (strategic bets). During firebreak: analytics shift to 80% Run work (platform health is “Run” work that keeps the lights on and improves operational excellence), 10% Grow, 10% Transform (only in-progress work wrapping up). After firebreak: return to 60% Grow, 30% Run, 10% Transform as planned feature work resumes.

This temporary portfolio shift demonstrates intentional platform health management rather than reactive firefighting. Leadership sees you’re not permanently abandoning feature work—you’re making a strategic two-sprint investment in foundation health that enables faster feature delivery in all subsequent sprints.

The analytics also create accountability. If firebreak sprints become too frequent (every quarter has a two-sprint firebreak), analytics reveal that platform health is consuming 30-40% of annual capacity rather than the intended 15-20%. This signals systemic problems: either you’re not allocating enough ongoing tech debt capacity and firebreaks are compensating, or architectural decisions are creating unsustainable maintenance burden.

Conversely, if you never run firebreaks and ongoing tech debt allocation never increases beyond 15%, but DORA metrics are degrading, analytics show that 15% isn’t sufficient given your technical debt accumulation rate. You need either more ongoing allocation or periodic firebreaks to catch up.

Running the Firebreak Sprint

Once the firebreak is planned and squads are allocated, execution requires discipline to maintain focus and track progress toward the objective.

Daily Progress Tracking: Burndown and Metrics

Unlike feature work where progress manifests as shipped functionality, firebreak progress is measured against the specific objective criteria. For security vulnerability remediation, track the burndown of critical issues: started at 347, down to 289 after day 1, down to 201 after day 3, targeting zero by end of sprint 2.

For DORA metrics improvement, track the metrics daily: deployment frequency currently 4/week, targeting >2/day (14/week). Change failure rate currently 18%, targeting <5%. Show the trend line approaching targets so teams see progress and maintain momentum.

For threading bug fixes, track services patched and deployed: 23 services total, 5 patched and deployed day 1, 12 patched and deployed day 3, all 23 deployed and verified by day 8.

This visible daily progress creates urgency and accountability. Teams see whether they’re on track to hit the objective by end of firebreak or whether they need to accelerate, cut scope, or extend the firebreak duration.

Daily standups during firebreaks focus entirely on progress toward the objective and blockers preventing progress. Not status updates about individual tasks, but “Are we on track to hit zero critical vulnerabilities by end of sprint? What’s blocking us? What help do we need?”

Blockers Escalated Immediately

Firebreaks have compressed timelines that don’t tolerate blockers sitting unresolved for days. When a squad hits a blocker (dependency conflict preventing update, unclear ownership of affected service, infrastructure access needed for deployment, breaking change requiring coordination), it escalates immediately to leadership for resolution.

The firebreak channel (#firebreak-security or similar) serves as the escalation point. “Squad B is blocked updating the payment service because we don’t have production deployment access. Need infrastructure team to grant permissions or perform the deployment.” Engineering leadership sees this within hours and resolves it same-day rather than the blocker sitting in a backlog for a week.

This escalation urgency is justified because every day of firebreak delay costs the organization both the firebreak capacity (squads not making progress toward the objective) and the ongoing accumulation of the problem the firebreak is meant to solve (vulnerabilities remaining exploitable, reliability issues causing incidents, slow deployments reducing velocity).

End-of-Firebreak Review: What Got Fixed, What’s Next

At the end of the firebreak sprint(s), the team conducts a comprehensive review of outcomes, not just outputs.

What got fixed: “We eliminated all 347 critical vulnerabilities. SonarQube dashboard shows zero critical issues. All 42 services are running updated dependencies with no critical or high-severity vulnerabilities. We verified this through automated security scanning and manual penetration testing.”

What metrics improved: “DORA metrics improved from 4 deploys/week to 18 deploys/week (exceeded target of 14/week). Change failure rate dropped from 18% to 3% (exceeded target of <5%). MTTR reduced from 6 hours to 25 minutes (exceeded target of <30min). Lead time reduced from 36 hours to 3 hours.”

What still needs attention: “We fixed critical and high-severity issues. We identified 127 medium-severity issues that remain in the backlog. We recommend allocating 20% ongoing tech debt capacity to address these over the next quarter, with another firebreak assessment in Q4 if accumulation accelerates again.”

Lessons learned: “The primary source of security vulnerabilities was delayed dependency updates. We’re implementing automated dependency update tooling to catch vulnerabilities earlier. The DORA metric improvements came primarily from pipeline automation and test parallelization. We’re documenting these improvements as new standards for all future services.”

The review creates institutional memory about what worked, what didn’t, and how to prevent the next crisis from reaching firebreak urgency.

After the Firebreak: Preventing the Next Crisis

Firebreaks are valuable crisis responses, but the goal is preventing crises that require firebreaks in the first place. Post-firebreak process changes reduce the likelihood of future firebreak necessity.

Ongoing Platform Health Allocation

The standard recommendation is allocating 15-20% of each sprint to technical health work: dependency updates, performance optimization, testing infrastructure, observability improvements, architecture refactoring. This ongoing allocation prevents accumulation that requires firebreaks. For a deeper discussion on categorising this work, see our guide on technical debt classification .

After a security firebreak, implement automated dependency update tooling (Dependabot, Renovate, Snyk auto-remediation) that creates PRs for security patches automatically, reducing the manual effort of staying current. Allocate capacity each sprint to reviewing and merging these automated updates.

After a DORA metrics firebreak, allocate ongoing capacity to maintaining the pipeline improvements made during the firebreak. Test suites that grew from 8 minutes to 12 minutes need pruning. Deployment automation that worked perfectly after the firebreak needs maintenance as new services are added.

After a reliability firebreak, allocate capacity to monitoring and observability improvements that catch performance degradation early, before it becomes a crisis requiring another firebreak.

The key is making this ongoing allocation explicit in the roadmap. Squad capacity shows “3/1” total, with “2.4/0.8” allocated to feature work and “0.6/0.2” allocated to platform health. This prevents the ongoing allocation from being squeezed out when feature pressure increases.

Platform Health Metrics Dashboard

Create a platform health dashboard that leadership reviews monthly (or quarterly) to assess whether platform health is on track or degrading toward firebreak territory.

The dashboard includes DORA metrics with trend lines, security vulnerability counts by severity with aging analysis, production incident frequency and MTTR trends, test suite runtime and test coverage trends, deployment success rate and rollback frequency, customer-facing performance metrics (p95 response times, error rates), and developer experience metrics (local build time, environment setup time).

Leadership reviews this dashboard asking: “Are any metrics trending in concerning directions? Should we increase ongoing tech debt allocation from 15% to 20%? Should we schedule a preventive firebreak before degradation reaches crisis levels?”

Preventive firebreaks scheduled when metrics trend toward yellow (concerning but not yet critical) are far more effective than reactive firebreaks scheduled when metrics are deep red (crisis requiring immediate response).

Trigger Thresholds for Next Firebreak

Define explicit thresholds that automatically trigger firebreak discussions so teams don’t wait until crisis forces action.

For security: “If SonarQube shows >100 critical vulnerabilities or >500 high-severity vulnerabilities, schedule firebreak assessment.”

For DORA metrics: “If deployment frequency drops below 1/day for two consecutive weeks, or change failure rate exceeds 10% for two consecutive weeks, schedule firebreak assessment.”

For reliability: “If production incidents increase by 50% quarter-over-quarter, or p95 response times exceed 500ms for two consecutive weeks, schedule firebreak assessment.”

These thresholds create objective decision criteria rather than subjective judgment about when platform health is “bad enough” to justify firebreak response.

Regular Firebreaks as Cultural Practice

Some high-performing engineering organizations schedule regular quarterly or semi-annual firebreaks proactively rather than reactively. Google’s “bug bash” weeks, Shopify’s “hack days,” and various forms of innovation time serve similar purposes—dedicated periods where normal feature work pauses for engineering excellence focus.

The advantage of scheduled firebreaks is predictability. Stakeholders know Q4 always includes a two-week engineering excellence sprint. They plan feature roadmaps accordingly. Teams allocate ongoing tech debt capacity less aggressively because they know the quarterly firebreak will address accumulation.

The disadvantage is reduced flexibility—sometimes Q4 doesn’t need a firebreak because platform health is strong, but you’re running one anyway because it’s scheduled.

The middle ground is scheduled firebreak assessments where leadership reviews platform health metrics quarterly and decides whether to run a firebreak. “Q2 platform health metrics are strong. We’ll skip the firebreak and allocate that capacity to features. Q3 assessment in August.” This combines predictability (quarterly assessment creates planning cadence) with flexibility (firebreak only happens if metrics justify it).

Common Mistakes with Firebreak Sprints

Even well-intentioned firebreaks often fail due to predictable mistakes that undermine their effectiveness.

Mistake 1: Letting “Urgent” Feature Work Creep Into the Firebreak

Sales escalates a customer-critical feature request. An executive asks “can’t we just squeeze this in since it’s urgent?” Teams start splitting capacity between firebreak work and “just this one urgent feature.” Before long, the firebreak is 60% firebreak work and 40% feature work, which means the firebreak objective doesn’t get achieved and feature work proceeds at reduced velocity. Nobody wins.

The solution is protecting firebreak time ruthlessly. “We’re in a firebreak sprint focused on security vulnerabilities. No feature work unless it’s a production outage requiring immediate fix. Your feature is important, but it waits until sprint 14 when we resume normal allocation. If that’s unacceptable, we can end the firebreak now and shift back to features—but then the security vulnerabilities remain unfixed and we’ll be back in crisis mode within weeks.”

Mistake 2: Scoping Too Much (Trying to Fix Everything)

Teams try to fix every technical problem in a single two-sprint firebreak: all security issues, all performance problems, all technical debt, all tooling improvements. The scope is overwhelming. Nothing gets completed. Teams declare the firebreak a failure.

The solution is ruthless scoping to the critical objective. “This firebreak addresses critical security vulnerabilities only. Performance problems are real but not addressed in this firebreak. They’re scheduled for Q3 ongoing allocation or a future firebreak if they reach critical mass.”

Mistake 3: Not Communicating Impact to Stakeholders Upfront

Teams announce “we’re doing a firebreak sprint” without explaining which features delay, by how much, or why it’s necessary. Stakeholders discover mid-sprint that their expected features aren’t happening. Trust erodes.

The solution is transparent communication before the firebreak begins showing the specific features that shift, the timeline impact, and the business rationale. “The retention feature shifts from May to June. The enterprise SSO feature shifts from June to July. We’re making this trade-off because 347 critical security vulnerabilities block our SOC2 audit, which blocks our enterprise sales pipeline.”

Mistake 4: Not Measuring Success (Can’t Prove Value)

Teams run the firebreak but don’t measure outcomes against the objective. They shipped work but can’t demonstrate that DORA metrics improved, vulnerabilities were eliminated, or reliability increased. Stakeholders question whether the firebreak was worth pausing features for.

The solution is objective-driven success criteria measured before and after. “Started with 347 critical vulnerabilities. Ended with zero. Started with 4 deploys/week. Ended with 18 deploys/week. Started with 18% change failure rate. Ended with 3%. Here’s the data proving the firebreak delivered measurable improvements.”

Mistake 5: Returning to 100% Feature Work Immediately After (Accumulation Restarts)

Teams complete the firebreak, celebrate the improvements, then immediately return to 100% feature allocation with zero ongoing platform health capacity. Within three months, vulnerabilities accumulate again, DORA metrics degrade again, and teams need another firebreak.

The solution is allocating 15-20% ongoing platform health capacity after the firebreak to maintain the improvements and prevent re-accumulation. “We fixed the foundation. Now we’re allocating 20% ongoing capacity to keep it healthy so we don’t need another crisis firebreak in six months.”

Conclusion: Strategic Investment in Engineering Health

Firebreak sprints feel scary to announce because they require telling stakeholders “we’re not shipping features for two weeks.” But the alternative—accumulating technical debt, security vulnerabilities, and platform reliability issues until velocity collapses entirely—is far more expensive than a two-sprint pause.

Technical debt compounds like financial debt. Each sprint you delay addressing critical issues, the problem grows, the interest accumulates, and the eventual fix becomes more expensive and disruptive.

Firebreak sprints are strategic investments in engineering health that prevent crisis-driven firefighting, reduce ongoing velocity drag from poor tooling and fragile systems, enable faster feature delivery in all future sprints through improved DORA metrics and developer experience, and prevent catastrophic failures (security breaches, production outages, compliance violations) that cost far more than two sprints of paused features.

RoadmapOne makes firebreak insertion practical through automatic sprint date recalculation when inserting new sprints, visual organizational alignment showing all squads focused on the firebreak objective, transparent timeline impact showing exactly which features delay by how much, and analytics tracking portfolio balance shift during firebreaks and return to normal after.

Most importantly, RoadmapOne enables honest stakeholder communication about firebreak trade-offs. Instead of hiding platform health work or pretending it doesn’t impact feature delivery, you show the explicit trade-off: “Two firebreak sprints shift these features by two weeks. In return, we eliminate security risks that block enterprise sales, improve deployment velocity by 3x, and prevent production reliability issues that churn customers.”

That’s not just better technical debt management. That’s strategic engineering investment that recognizes the foundation matters as much as the features you build on it.

References and Further Reading

- Capacity-Based Roadmap Planning - Understanding capacity allocation for firebreak sprints

- Time-Boxed Discovery - Similar principles of focused, time-boxed effort applied to platform health

- Objective Prioritisation Frameworks - Prioritizing which platform health issues justify firebreak responses

- DORA Research: Accelerate: State of DevOps Reports - The science behind DORA metrics and high-performing teams

- SonarQube - Code quality and security vulnerability scanning

- Snyk - Security vulnerability detection and remediation for dependencies