How to Build a Product Roadmap That Actually Works

The Human Work Most Teams Skip

Your last roadmap failed. Not because your tools were wrong or your data was inadequate, but because nobody actually believed in it. The CFO nodded politely while mentally overriding your priorities. Sales treated it as a wish list. Engineering saw it as fiction.

Here’s the uncomfortable truth: most roadmaps die not from poor planning, but from skipping the human work of building genuine consensus. You can have the most sophisticated roadmapping software in the world, but if your CFO doesn’t understand why you’re prioritizing customer retention over new features, or if your sales team isn’t bought into your capacity constraints, your roadmap will be dead on arrival.

In this guide, I’ll walk you through a proven five-step process for building a software product roadmap that stakeholders will actually stand behind. This isn’t about creating a perfect plan—it’s about crafting the least worst plan that everybody can tolerate, understand, and commit to delivering.

What Makes a Good Product Roadmap?

Before we dive into the mechanics of building a product roadmap, let’s establish what we’re actually trying to create.

A good product roadmap is not a list of features with dates attached. That’s a release plan, and it’s fundamentally different. A roadmap is a strategic document that sits within the vision → strategy → roadmap hierarchy and communicates how you’ll allocate your most constrained resource—your development capacity—to achieve measurable business outcomes over the next 12-18 months. This is why many teams structure their roadmaps around OKRs (Objectives and Key Results) rather than feature lists.

The best roadmaps share several characteristics:

Outcome-focused, not output-focused. Your roadmap should articulate the business results you’re trying to achieve, not just what you’re building. “Increase trial-to-paid conversion from 15% to 25%” is an objective worth discussing with your CFO. “Build an improved onboarding flow” is just a task.

Transparently shows trade-offs. When you allocate three developers to objective A for Q2, everyone can see that those developers aren’t available for objectives B, C, or D. This visibility forces honest conversations about priorities.

Creates alignment without requiring agreement. Not everyone will get what they want. That’s fine. What matters is that everyone understands why the priorities landed where they did and commits to the plan anyway.

Remains flexible enough to adapt. Markets change. Competitors move. Customer needs evolve. Your roadmap should communicate strategic intent, not make immutable promises.

Now let’s talk about how you actually build one.

Step 1: Identify Business Objectives and Outcomes

The foundation of any good product roadmap is a clear understanding of what your organization actually needs to achieve. Notice I didn’t say “what your organization wants to build”—that comes later, if at all.

Start by working with colleagues across marketing, sales, technology, finance, operations, customer success, compliance, and any other department with skin in the game. Your goal is to generate a comprehensive list of potential business objectives—the measurable outcomes that would materially impact your company’s performance or sustainability.

What Makes a Good Objective?

Not all objectives are created equal. The best objectives share these characteristics:

Business-outcome oriented. A good objective is recognizable and meaningful to your CEO, CFO, and board members. Examples include “Increase annual recurring revenue by £2M,” “Reduce customer acquisition cost below £50,” “Achieve SOC 2 compliance by Q3,” or “Reduce support ticket volume by 40%.”

These are fundamentally different from internal efficiency goals like “Deploy to production twice per week” or “Reduce technical debt.” Those internal objectives have their place, but they’re a means to an end, not ends in themselves. If you’re going to include internal effectiveness objectives, tag them explicitly so stakeholders understand they don’t directly deliver customer value.

Measurable and specific. Vague aspirations like “Improve customer experience” aren’t objectives—they’re themes. Transform them into something measurable: “Increase Net Promoter Score from 42 to 55” or “Reduce customer-reported errors from 2.3% to below 1%.”

Time-bound. When do you need to achieve this outcome? Is it crucial for Q1, or can it wait until H2? This temporal element becomes critical when you start allocating capacity.

Achievable with reasonable effort. An objective that would consume your entire engineering organization for 18 months probably isn’t one objective—it’s a program containing multiple objectives that should be broken down and sequenced.

As you’re collecting objectives from across the organization, expect to generate 20, 30, maybe even 50+ potential outcomes. This is good. Cast the net wide. You want everyone’s priorities on the table, even if there’s no chance you’ll deliver them all.

Choosing a Prioritization Framework

Once you have your long list of objectives, you need a systematic way to evaluate them. This is where prioritization frameworks come in.

There are dozens of approaches—RICE , ICE , MoSCoW , WSJF , Value vs. Complexity , and many others . The specific framework matters less than having some consistent way to evaluate objectives against each other.

Most frameworks ask you to assess objectives across a few key dimensions:

- Value: What business impact will this create? Revenue increase? Cost reduction? Risk mitigation?

- Effort: How much engineering capacity will this consume?

- Urgency: What happens if we delay this? Is there a regulatory deadline or market window?

- Strategic alignment: How well does this support our long-term vision?

- Risk: What’s the likelihood of success? What could go wrong?

As the Chief Product Officer or product leader, your job at this stage is to work with your colleagues to do a very high-level first pass at prioritizing the objectives. You’re not making final decisions—you’re creating a starting point for discussion. Apply your chosen framework consistently, and don’t overthink it. The goal is to surface which objectives are clearly high priority, which are clearly low priority, and which fall into the contentious middle ground.

There will always be “strategic” objectives that don’t necessarily lend themselves to this kind of prioritisation. It’s already a cliche but “doing something with AI” might be important for your IPO opportunities.

Initial High-Level Prioritization

After your first prioritization pass, you should start to see patterns emerge. Perhaps 8-10 objectives cluster at the top as clearly essential. Another 20-30 are obviously lower priority. The remaining objectives sit in the murky middle where reasonable people might disagree.

This is exactly where you want to be before involving leadership. You’ve done enough analysis to make the workshop productive, but not so much that you’re wedded to specific conclusions.

Make your prioritization visible and transparent. Use a simple scoring system that shows how each objective performed against your framework criteria. This data becomes the foundation for your next step: securing leadership alignment.

Step 2: Align Leadership on Strategic Priorities

Now comes the first critical piece of human work: getting your executive team aligned on which objectives actually matter most.

Preparing for the Executive Workshop

Before you schedule a workshop with your executive committee, do some political groundwork. Meet with key stakeholders individually to preview the list of objectives. Your goals in these conversations are to:

Ensure nobody is surprised. When the CFO scans your prioritized list and doesn’t see their top objective anywhere, they’re going to be upset. Better to have that conversation before the workshop than during it.

Understand each stakeholder’s non-negotiables. Every executive has one or two objectives they consider absolutely critical. Identify these early so you can structure the workshop discussion accordingly.

Pressure-test your prioritization. You might think compliance with new data protection regulations is medium priority. Your Head of Legal might have a very different view, backed by solid arguments you hadn’t considered.

Once you’ve done this preparatory work, schedule a 90-120 minute workshop with your executive committee. This session has a simple agenda:

- Review the complete list of potential objectives (10 minutes)

- Confirm everyone sees their priorities represented (10 minutes)

- Walk through your prioritization framework and initial scoring (20 minutes)

- Discuss the ranking, focusing on significant disagreements (50-80 minutes)

- Identify next steps and areas requiring more data (10 minutes)

Running the Prioritization Discussion

Start the discussion section by explicitly calling out the top 10-15 objectives from your prioritization. Ask: “Does anyone strongly disagree with these being our highest priorities?”

This framing is intentional. You’re not asking for unanimity or even agreement. You’re checking for strong disagreement—the kind that would prevent someone from supporting the roadmap.

When disagreements surface (and they will), dig into the reasoning. Often, what looks like a disagreement about priorities is actually a disagreement about facts, assumptions, or definitions. Perhaps marketing assumes an objective requires two developers for one quarter, while engineering believes it needs five developers for six months. That’s not a priority disagreement—it’s an estimation disagreement that requires more discovery.

Be prepared for some objectives to move up or down significantly based on information you didn’t have. That’s good. The goal isn’t to be right in your initial prioritization—it’s to facilitate a data-informed conversation.

Achieving Consensus (Not Unanimity)

Here’s a crucial point many product leaders miss: you’re not trying to get everyone to agree that the prioritization is perfect. You’re trying to get everyone to a place where they can live with it.

This is what I mean by “the least worst plan that everybody can tolerate.” Your Head of Sales might still believe that the three objectives you’ve prioritized for Q4 should be moved to Q1. But if they understand why those Q1 slots are occupied by compliance and technical stability work, and if they can see their objectives will get resourced eventually, they can support the plan.

By the end of this workshop, you should have:

- A prioritized list of 20-30 objectives that reflect executive priorities

- Broad (not universal) agreement that the top 10-15 objectives are the right starting point

- A list of questions requiring more discovery or estimation

- Clear owners for objectives that need more refinement

You should not have a perfect, final prioritization. You should have enough alignment to start building an actual roadmap.

Step 3: Build Your Alpha Roadmap

Now the real work begins. You’re going to take your prioritized list of objectives and turn it into an actual roadmap showing which teams will work on what, and when.

Setting Up Your Squad Structure

The first step is defining your delivery teams—usually called squads in modern product organizations.

If you already have an established team structure, start there. You likely have teams organized around product areas, customer segments, or technical domains. List them out.

If you’re building a team structure from scratch or considering reorganization, think carefully about squad composition. The ideal squad is small enough to maintain communication efficiency but large enough to be genuinely cross-functional —typically 5-9 people including engineers, designers, product managers, and any other disciplines needed for autonomous delivery.

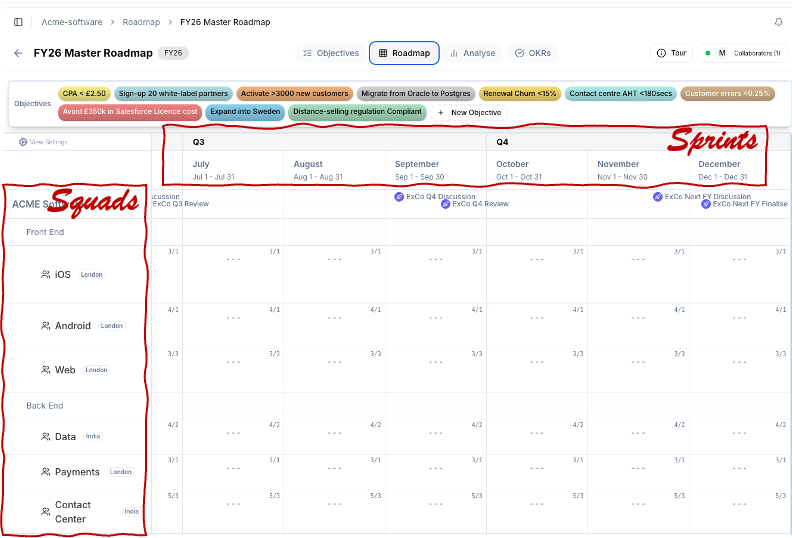

Enter your squads as rows in your roadmap. Your sprints or time periods (typically quarters or months) become columns. Each intersection of a squad and a time period is a “WIP”—a Work in Progress slot where you can allocate objectives.

Allocating Objectives to Teams

Now start dragging and dropping your highest-priority objectives onto specific squads and time periods.

This is where your roadmap becomes real. You’re making concrete decisions about who will work on what. As you do this, several patterns will emerge:

Capacity constraints become immediately visible. When Squad A has three high-priority objectives competing for Q1, you’re forced to make trade-offs. Can one objective wait until Q2? Can you split it across Q1 and Q2? Does it need a different squad?

Dependencies surface naturally. You might realize that objective B can’t start until objective A completes because they need the same technical infrastructure. Or that the marketing campaign for objective C requires objective D to ship first.

Team structure gaps appear. Perhaps you need a dedicated security team to handle compliance objectives, or you realize your existing teams are too specialized to tackle cross-functional work effectively.

Don’t aim for perfection here. This is an alpha version—a first draft meant to stress-test your assumptions and surface issues.

Balancing Workload and Capacity

As you allocate objectives, pay attention to workload distribution. Are some squads completely overloaded while others have capacity gaps? Remember too that teams don’t have 100% capacity for feature work—there’s always keeping-the-lights-on (KTLO) work to account for. Imbalances might indicate:

- Misalignment between team skills and objective requirements

- Opportunities to restructure teams for better efficiency

- Need for additional hiring or contracting

- Objectives that could be descoped or deferred

Your alpha roadmap should give you a rough sense of whether your prioritized objectives can realistically be delivered with your current team structure and capacity. If you’ve allocated 50 objectives to 10 squads over 4 quarters, and simple math suggests that’s 5 objectives per squad per quarter when they can typically deliver 2-3, you have a capacity problem that needs addressing.

This is exactly what you want to discover now, not six months into execution.

Step 4: Iterate and Refine Your Roadmap

With an alpha roadmap in hand, you enter what I call “the art of roadmapping”—a series of iterative refinements where you gradually evolve from a directional sketch to a workable plan.

This is the most important step, and the one most organizations rush through or skip entirely. Don’t make that mistake.

Validating with Product and Tech Leadership

Your first priority is pressure-testing the roadmap with your product and engineering leaders—the people who actually have to deliver it.

Bring your squad leads, engineering managers, and senior product managers together. Walk them through the roadmap. Then ask the hard questions:

- “Is this realistic given your team’s capacity and capabilities?”

- “What am I missing or underestimating?”

- “Which objectives are actually much bigger than they look?”

- “Which dependencies am I not seeing?”

Listen carefully to the feedback. When an engineering lead says “that objective will take three times longer than you think,” don’t argue. Ask why. Often they’ve spotted technical complexity or dependencies that weren’t obvious during initial planning.

Be prepared to move objectives between quarters, reassign them to different squads, or break large objectives into smaller phases. This is exactly the kind of refinement that turns a theoretical roadmap into an executable plan.

Using Analytics to Balance Your Portfolio

Once your roadmap is reasonably realistic from a capacity perspective, shift your attention to strategic balance.

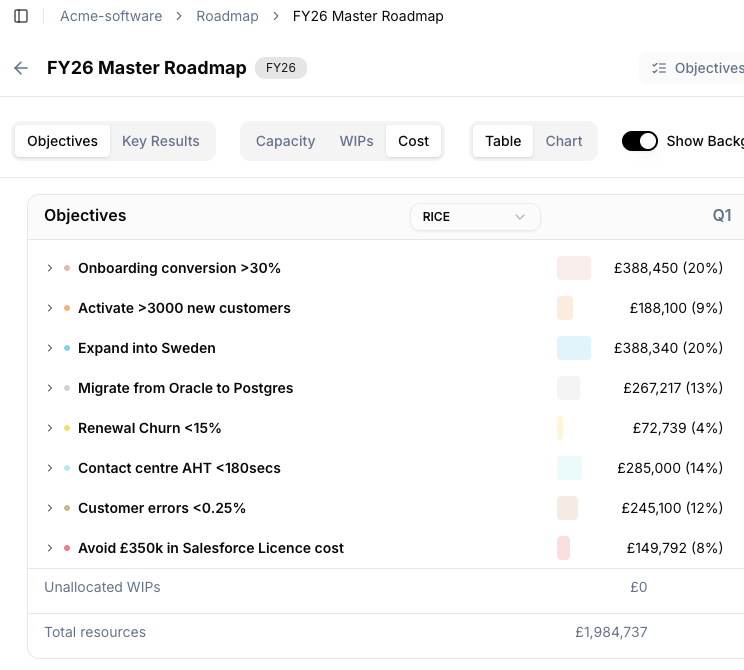

Most roadmapping tools offer analytics that show you how your capacity is distributed across different dimensions. You might see:

- 60% of Q1 capacity allocated to revenue growth objectives

- 25% allocated to customer retention

- 10% allocated to compliance and risk management

- 5% allocated to technical debt and platform improvements

These numbers tell a story about your strategic priorities. Are they the right story?

Perhaps seeing “5% on technical debt” triggers alarm bells for your CTO, who believes you need 15-20% to maintain platform stability. Or maybe your CFO is surprised that only 10% of capacity goes to cost reduction when that’s supposedly a major strategic priority.

Use these analytics to facilitate conversations about portfolio balance. There’s no universally “correct” distribution—it depends entirely on your business context, maturity stage, and strategic goals. But making the distribution visible allows stakeholders to debate it explicitly rather than discovering misalignment later.

Objective Tagging for Portfolio Balance

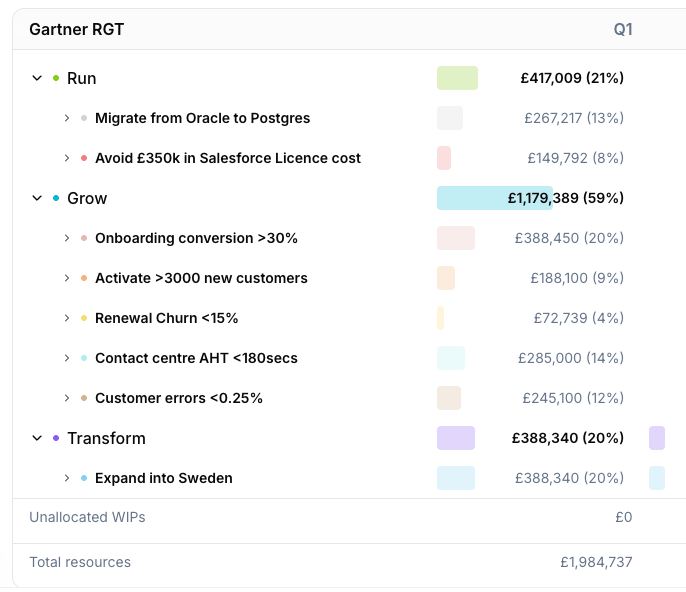

One powerful way to analyze your roadmap is through objective tagging frameworks . These frameworks categorize objectives using established mental models that help stakeholders think about strategic balance.

For example, you might tag objectives using the “Run, Grow, Transform” framework:

- Run: Keep current operations working (customer support, bug fixes, compliance)

- Grow: Expand existing business lines (new features for current customers, market expansion)

- Transform: Create new capabilities or business models (new products, platform changes, strategic pivots)

When you visualize that 80% of your capacity goes to “Run” activities and only 5% to “Transform,” that might spark an important strategic discussion. Is that the right balance for a growth-stage company? Maybe yes, maybe no—but at least you’re having the conversation explicitly.

Other useful tagging frameworks include:

- Customer acquisition vs. retention vs. monetization

- Customer-facing vs. internal efficiency

- Strategic initiatives vs. operational necessities

- Revenue generation vs. cost reduction vs. risk mitigation

The specific frameworks matter less than establishing a shared language for discussing trade-offs.

Adding Key Results Strategically

At some point in your iteration process, you’ll want to add more specificity about how you’ll achieve each objective. This is where key results come in.

In the SVPG Product Model , leadership allocates objectives to teams, but teams are empowered to determine their own key results—the specific, measurable outcomes they’ll target to achieve the objective.

This is a crucial distinction. When you tell a squad “Improve trial conversion” and let them define key results like “Reduce time-to-first-value from 45 minutes to 15 minutes” and “Increase feature discovery rate by 40%,” you’re empowering them to solve the problem rather than dictating the solution.

That said, don’t get carried away adding key results to every objective on your roadmap during this planning phase. Focus on key results for:

- Objectives starting in the next 1-2 quarters

- High-risk or strategically critical objectives where alignment on success metrics is essential

- Objectives where different stakeholders have different assumptions about what success looks like

For objectives six months out, you probably don’t need detailed key results yet. Those will evolve as teams move into discovery and execution.

Securing Cross-Functional Commitments

Here’s where roadmapping becomes truly collaborative. Your roadmap isn’t just a product and engineering document—it’s a company-wide commitment about how you’ll allocate resources to achieve outcomes.

That means other departments need to make corresponding commitments.

If your roadmap shows Squad 3 delivering “Increase enterprise deal size from £50K to £100K” in Q2, your sales team needs to commit that they’ll actually close those larger deals once the capability exists. If they’re not confident they can sell it, or if their compensation structure doesn’t incentivize larger deals, or if the market doesn’t want that offering, then that objective shouldn’t be on your roadmap.

Similarly, if you’re prioritizing “Expand into German market” in Q3, marketing needs to commit to localized campaigns, sales needs German-speaking reps, and finance needs to model the investment and expected return.

Have explicit conversations with each functional leader:

“If we deliver X, will you do Y? And if we do X and you do Y, will we achieve outcome Z?”

These commitments are crucial. They transform your roadmap from a wishlist into an integrated business plan.

This is also where you’ll discover hidden issues. Perhaps marketing can’t commit to a German expansion in Q3 because they need six months of lead time to build campaigns. Now you know you need to either delay the product work or accelerate the marketing prep.

This back-and-forth takes time. You might iterate through 5, 10, or even 15 versions of your roadmap before all the pieces align. That’s normal and healthy. Each iteration brings you closer to a plan that can actually work in reality.

Step 5: Achieve Final Sign-Off and Alignment

After weeks of iteration, analysis, and cross-functional negotiation, you’re ready for the final step: securing executive sign-off on your roadmap.

The Final Executive Review

Schedule another executive committee meeting to review the refined roadmap. This meeting should feel very different from your initial prioritization workshop.

By now, each executive has been involved in shaping the roadmap. They’ve seen drafts. They’ve negotiated about their priorities. They’ve made commitments about what their teams will do to support delivery. There should be no surprises in this room.

Walk through the roadmap methodically:

- Show the squad allocations and timeline

- Present the analytics showing strategic distribution (percentage by objective type, by business area, by customer segment, etc.)

- Highlight key dependencies and cross-functional commitments

- Call out the 2-3 areas where trade-offs remain contentious

- Review the assumptions and risks that could invalidate the plan

Then ask the critical question: “Can everyone in this room stand behind this roadmap?”

Note the phrasing. Not “Does everyone love this roadmap?” or “Is everyone thrilled with their priorities?” Those are unrealistic expectations. The question is whether each leader can publicly support the plan, communicate it to their teams, and commit to delivering their part.

Standing Behind the Plan Together

This moment of collective commitment is what separates successful roadmaps from failed ones.

When your Head of Sales tells their team “Product is prioritizing enterprise features in Q2, so we’re focusing on mid-market deals in Q1”—and they do that without undermining the decision or suggesting product got it wrong—that’s alignment.

When your CFO asks the board “Why aren’t we investing more in cost reduction?” and your CEO responds “We had that debate, looked at the data, and decided growth objectives need to come first this year”—that’s standing behind the plan.

This doesn’t mean debate stops. Roadmaps should be living documents that evolve as you learn and as circumstances change. But it does mean that for now, everyone agrees this is the plan you’re committing to.

If you can’t get this alignment in the final review meeting, don’t push through anyway. That’s a disaster in the making. Instead, identify what’s blocking consensus. Do you need more data? Is there a fundamental disagreement about strategy that needs escalation to the board? Is someone feeling like their voice wasn’t heard during the process?

Address those concerns, even if it means another round of iteration. It’s better to take an extra two weeks to get genuine buy-in than to launch a roadmap nobody actually supports.

The Role of Roadmapping Tools

Throughout this guide, I’ve focused on the process and human dynamics of building a product roadmap rather than the tools. That’s deliberate.

The roadmapping process I’ve described will work whether you use a sophisticated platform like RoadmapOne , a spreadsheet, or sticky notes on a wall. The process is about people, conversations, trade-offs, and commitments.

That said, having the right tool makes this process dramatically easier.

When you can drag-and-drop objectives onto squad rows and instantly see capacity implications, iteration happens faster. When stakeholders can view real-time analytics showing how resources are distributed across strategic priorities, conversations become more data-informed. When everyone can see the same roadmap and understand the same trade-offs, alignment becomes achievable.

Good tools enable transparency. They make trade-offs visible. They force specificity about what you’re committing to and what you’re not. They create a shared source of truth that everyone references in decision-making.

So while you don’t need fancy software to build a roadmap, having a purpose-built platform transforms what’s possible. It’s the difference between possible and practical, between theoretically sound and actually workable.

Common Pitfalls to Avoid

Before we wrap up, let me highlight some common mistakes that derail roadmap development:

Skipping stakeholder engagement until the end. If the first time your CFO sees the roadmap is in the final sign-off meeting, you’ve failed. Involve stakeholders throughout the process.

Confusing a roadmap with a release plan. Your roadmap is strategic. It shows what outcomes you’re pursuing and why. A release plan is tactical—it shows what features ship when. Don’t conflate them.

Optimizing for perfection instead of workability. There is no perfect roadmap. There is only the least worst plan that everyone can support. Aim for good enough, not perfect.

Treating the roadmap as set in stone. Markets change. Competitors move. Customer needs evolve. Your roadmap should too. Build in regular review points to reassess priorities.

Letting the loudest voice win. Use frameworks and data to make prioritization more objective. Don’t let organizational politics determine which objectives get resourced.

Ignoring capacity constraints. Wishful thinking doesn’t create more developers. If your roadmap assumes delivery capacity you don’t have, it will fail. Be ruthlessly realistic. Our guide to capacity-based roadmap planning explores this in depth.

Forgetting that roadmapping is fundamentally about people. Tools, frameworks, and processes matter. But ultimately, your roadmap succeeds or fails based on whether the humans in your organization understand it, believe in it, and commit to delivering it.

Conclusion

Building a product roadmap that works—that genuinely aligns stakeholders, guides teams, and survives the chaos of execution—is hard work. It requires strategic thinking, analytical rigor, political savvy, and genuine collaboration across your organization.

But when you get it right, the results are transformative. Instead of endless debates about priorities, you have a shared plan. Instead of teams working at cross-purposes, you have coordinated effort toward common objectives. Instead of stakeholders discovering in Q3 that their Q1 priorities never got resourced, everyone knows what’s happening and why.

The five-step process outlined in this guide—identifying objectives, aligning leadership, building an alpha roadmap, iterating to refine it, and securing final commitment—provides a proven path from chaos to clarity.

Remember: you’re not trying to create a perfect roadmap. You’re trying to create the least worst plan that everybody can tolerate. That might sound cynical, but it’s actually profound. In complex organizations with competing priorities and constrained resources, achieving a plan that everyone can stand behind is a remarkable accomplishment.

Now go build a roadmap that actually works. Your teams, your stakeholders, and your customers are waiting.