From Objectives to Key Results: How Product Managers Lead the Discovery Breakdown

The email from your CEO arrives Monday morning: “Retention has dropped from 68% to 65% over the past two months. We need to reverse this trend. Make increasing retention from 65% back to 75% a top priority objective for your team this quarter.”

You now have an objective. What you don’t have are key results—the specific, measurable outcomes that will actually move retention from 65% to 75%.

Is it reducing time-to-first-value that drives retention? Improving onboarding completion rates? Fixing specific friction points in the core user journey? Increasing product engagement frequency? Reducing early churn by addressing the top reasons users leave?

These aren’t rhetorical questions. They’re the most important questions your team will answer this quarter, because choosing the wrong key results means spending months of engineering effort on solutions that don’t move retention, burning capacity while the business outcome you’re supposed to deliver remains stuck.

This is where product management leadership actually matters. Not in writing requirements. Not in managing backlogs. Not in running standup meetings. Leadership shows up in the collaborative discovery process where product managers facilitate teams in breaking down broad business objectives into specific, validated, measurable key results that teams genuinely believe will deliver the outcome.

This moment—the objective-to-key-result breakdown during discovery—separates empowered product teams from feature factories. Let’s explore how to lead it effectively.

The SVPG Product Model: Leadership Allocates, Teams Define Solutions

Before diving into the discovery process, it’s critical to understand the product operating model that makes this breakdown work: leadership allocates objectives to teams, and empowered teams determine the key results and solutions that will deliver those objectives.

This model, extensively described by Marty Cagan and Silicon Valley Product Group (SVPG), flips the traditional command-and-control approach where leadership defines both the problem (objective) and the solution (key results and features). Instead, leadership focuses on outcomes while teams focus on solutions.

Leadership’s role is allocating objectives that matter to the business. “Increase customer retention from 65% to 75%.” “Reduce customer acquisition cost by 30%.” “Expand into the European market with 50 new enterprise customers.” “Achieve SOC2 compliance by end of Q3.” These objectives can be further categorised using objective tagging frameworks like Run-Grow-Transform . These are business outcomes that executives, boards, and stakeholders care about—metrics that directly impact revenue, growth, profitability, or strategic positioning.

These objectives are challenging, sometimes ambiguous, and genuinely important. That’s what makes them appropriate objectives rather than tactical tasks. If leadership could easily define the solution, it wouldn’t require an empowered product team. It would just be a feature request.

The team’s role is determining how to achieve those objectives. Which specific outcomes (key results) will move the broader objective? Which solutions (features, improvements, fixes) will drive those outcomes? This is where product managers, designers, and engineers bring their expertise in customer problems, technical possibilities, and creative problem-solving.

The critical insight is that teams who understand customer problems deeply and who test solutions through iterative discovery almost always find better approaches than leaders who define solutions from the top down without that customer proximity and technical context.

But this empowerment only works if teams actually engage with the objective, explore the problem space thoroughly, validate assumptions with customers, and commit to key results they genuinely believe will deliver the outcome.

That collaborative discovery process—where broad objectives break down into specific key results—is where product managers demonstrate leadership.

Discovery: The Collaborative Workshop for Key Result Definition

Discovery isn’t just about validating whether customers want specific features. It’s the strategic workshop where teams figure out which levers actually move business objectives and commit to the specific key results that represent testable hypotheses about how to achieve the objective.

When leadership allocates an objective like “Increase retention from 65% to 75%,” discovery answers several critical questions before teams commit to delivery work:

What are the real drivers of retention in our product? Not what we assume drives retention, but what actually matters to customers. Do they stay because they’ve achieved meaningful value quickly? Because they’ve built habits around core workflows? Because they’ve invested data or integrations that create switching costs? Because they find the product delightful rather than just functional?

Which of those drivers are we currently under-serving? If time-to-first-value is a key retention driver but our current onboarding takes 48 hours when users need results in 4 hours, that’s a specific gap. If activation completion is a driver but only 40% of trial users complete activation, that’s another gap.

Which interventions would close those gaps? Could we reduce time-to-first-value with better onboarding, smarter defaults, guided workflows, or template solutions? Could we increase activation completion with progressive disclosure, contextual help, or simplified initial setup?

Which interventions will customers actually respond to? Not what sounds logical in a strategy document, but what tests positively with actual users. Do customers care more about faster time-to-value or about richer feature education? Does simplifying activation drive completion better than incentivizing it?

Discovery is where these questions get answered through customer interviews, prototype testing, assumption validation, and collaborative workshops where the full product trio (PM, design, engineering) synthesizes insights into specific, measurable key results.

The output of discovery isn’t a feature list. It’s a set of key result commitments: “Based on customer research and prototype testing, we believe these three key results will move retention from 65% to 75%: Reduce time-to-first-value from 48 hours to 4 hours, Increase activation completion from 40% to 70%, Reduce early churn by fixing the top 5 onboarding friction points.”

These key results become the team’s hypothesis about how to deliver the objective. Discovery provides enough confidence to commit. Delivery tests the hypothesis at scale.

The Product Manager’s Leadership Opportunity

This objective-to-key-result breakdown is where product managers can demonstrate genuine leadership—far more impactful than the administrative PM work that consumes too many PMs’ time.

Facilitating Collaborative Discovery Workshops

The best PM leadership doesn’t happen by one person disappearing for a week to “figure out the key results” then presenting conclusions to the team. It happens through collaborative workshops where PMs facilitate teams in collectively exploring the problem space, synthesizing insights, and co-creating key results.

Effective facilitation means bringing together the right people (product trio plus relevant cross-functional stakeholders like customer success, sales, data analysts), structuring the conversation around insights not opinions (start with customer interview synthesis, prototype test results, usage data analysis), asking generative questions that open up problem space (“What surprised you in the customer interviews? What patterns did we see across multiple customers? What didn’t we hear that we expected to?”), and guiding the team toward specific, measurable key result hypotheses (“So if we believe time-to-first-value is the key driver, what’s the specific metric we think will move retention? By how much?”).

Great facilitation creates space for everyone’s expertise. Engineers bring technical constraints and possibilities. Designers bring user psychology and behavioral insights. PMs bring business context and strategic priorities. Customer-facing teams bring real-world user struggles. The synthesis of these perspectives produces better key results than any individual could define alone.

Engaging the Team with the Opportunity

One of the most underrated PM skills is making teams care about solving the problem. Not just accept it as an assigned task, but genuinely engage with the opportunity to create customer impact.

This means painting a compelling picture of the customer problem, not just the business metric. Instead of “We need to increase retention from 65% to 75% because the board is concerned about churn,” try “We’re losing 35% of customers within three months. We interviewed churned customers. They all say the same thing: they signed up excited about solving X problem, but our onboarding was so confusing they never got to the value they came for. We’re failing customers who want to love our product but can’t figure out how to get started. That’s a solvable problem.”

The metric (65% to 75% retention) matters, but the human problem (customers failing to realize value through confusing onboarding) is what engages creative problem-solving.

Making the team care also means connecting the objective to impact beyond business metrics. How does solving this change customers’ lives? How does it differentiate us from competitors? How does it set up future opportunities if we nail this?

Teams that care about solving customer problems bring their best creative thinking to discovery. Teams that see objectives as administrative obligations from leadership bring minimum viable effort.

Guiding the Breakdown from Objectives to Key Results

While discovery is collaborative, PMs guide the process from broad objective to specific key results through structured thinking about which metrics actually represent progress toward the objective and which metrics teams can realistically influence.

This guidance often involves redirecting teams from activity metrics to outcome metrics. When teams propose key results like “Launch improved onboarding flow” or “Conduct 50 customer interviews” or “Ship mobile redesign,” those are outputs and inputs, not outcomes. The PM redirects: “Those are things we’ll do. What outcome do we expect from the improved onboarding flow? How will we measure whether it worked?”

It also involves calibrating ambition. If the objective is increasing retention from 65% to 75%, key results that collectively only move retention to 68% aren’t sufficient. The PM helps teams calibrate: “If we achieve all three of these key results, do we believe retention reaches 75%? Or do we need more ambitious targets, or additional key results?”

Finally, it involves ensuring measurability. Teams sometimes propose key results like “Improve user satisfaction with onboarding” or “Make activation easier.” The PM pushes for specificity: “How will we measure satisfaction? What specific satisfaction score, measured how? What does ’easier activation’ mean numerically—completion rate? Time to complete? Error rate?”

This guidance doesn’t mean PMs unilaterally define key results. It means PMs ensure the collaborative process produces key results that are specific, measurable, outcome-focused, ambitious enough to deliver the objective, and aligned with what discovery validated.

Building Psychological Safety for Experimentation

Discovery only works when teams feel safe exploring ideas, testing assumptions, and discarding bad concepts quickly. PMs create the environment where learning is valued over being right.

This means celebrating invalidated assumptions as valuable learning. “We thought time-to-first-value was the key retention driver. Customer interviews showed it’s actually activation completion. Thank you for discovering this before we wasted months building the wrong solution.”

It means making explicit that discovery exists to reduce risk. “We’re spending two sprints discovering which key results will actually move retention specifically so we don’t waste six months building features that don’t work.”

It means giving teams permission to kill their own ideas. “If discovery reveals that your proposed key result won’t move retention, speak up. We’ll pivot to what actually works. Nobody’s judging you for changing your mind when evidence emerges.”

Psychological safety sounds soft. It’s actually the difference between teams that bring honest assessments of what’s working versus teams that hide problems, defend failing approaches, and waste capacity on solutions they know won’t work but can’t admit publicly.

Connecting Discovery Insights to Roadmap Decisions

PMs translate what teams learn during discovery into informed roadmap planning, resource allocation, and stakeholder communication.

This means updating objectives based on discovery insights. It also means understanding how discovery feeds into capacity-based planning —if you discover the objective requires more effort than anticipated, you need to know whether capacity exists. If discovery reveals the original objective is unrealistic or misdirected, the PM escalates to leadership: “We set out to increase retention from 65% to 75% by improving onboarding. Discovery showed that onboarding isn’t the primary retention driver—product feature depth is. Should we pivot the objective, or should we stick with onboarding improvements knowing they’ll move retention from 65% to 68% but won’t hit 75%?”

It means allocating appropriate delivery capacity based on what discovery validated. If discovery produced high-confidence key results with clear implementation paths, the PM allocates delivery capacity immediately. If discovery surfaced uncertainty that needs additional validation, the PM allocates another discovery sprint rather than jumping to delivery on shaky assumptions.

It means communicating discovery outcomes to stakeholders in ways that build trust in the process. Instead of “We didn’t ship anything in two sprints because we were in discovery,” explain “We invested two discovery sprints validating which specific interventions would move retention. We discovered time-to-first-value is the key driver. We validated that reducing it from 48 hours to 4 hours increases retention by 12 percentage points in prototype testing. We’re now confident that six delivery sprints focused on this key result will deliver the objective. Here’s the roadmap showing discovery, delivery, and expected impact timeline.”

This translation from discovery insights to roadmap reality is core PM work that often gets neglected when PMs see themselves as backlog managers rather than strategic facilitators.

From Broad Objective to Specific Key Results: A Worked Example

Let’s walk through a concrete example of how the objective-to-key-result breakdown unfolds during discovery.

The Objective: Leadership allocates this objective to the growth team: “Increase trial-to-paid conversion rate from 15% to 25%.”

This is a clear business outcome. Trial-to-paid conversion directly impacts revenue growth, reduces customer acquisition costs (fewer trial users needed to generate a paid customer), and validates product-market fit (higher conversion means the product delivers value users are willing to pay for).

But the objective doesn’t specify how to achieve it. Is conversion low because the trial period is too short? Because users don’t reach the aha moment during trial? Because pricing is confusing? Because the upgrade flow is broken? Because users encounter feature limits that frustrate them? Because competitors offer more generous free tiers?

Discovery must answer: which specific key results will move trial-to-paid conversion from 15% to 25%?

Week 1: Customer Interview Blitz

The product trio (PM, designer, lead engineer) plus a data analyst spend Week 1 conducting intensive customer interviews with three distinct cohorts: current customers who converted from trial to paid (understanding what drove their conversion), trial users who didn’t convert (understanding what prevented conversion), and customers who converted but considered canceling during trial (understanding what almost stopped them).

Patterns emerge quickly. Converting customers consistently describe an “aha moment” where the product solved a problem they’d been struggling with for months. This aha moment happened within the first 48 hours of their trial for most converters. For non-converters, either they never reached the aha moment, or it took 5-7 days to experience it—but by then they’d already mentally moved on to evaluating other solutions.

Nearly every converting customer mentions completing the initial activation flow (connecting their data source, inviting team members, setting up their first workflow) as the gateway to experiencing value. Conversion rates for users who complete activation are 45%. Conversion rates for users who don’t complete activation are 3%.

Non-converting users describe the activation flow as “confusing,” “too long,” and “requiring information I didn’t have available.” Many abandoned activation partway through and never returned. Others completed activation but took 4-5 days to do it, by which point they’d lost momentum.

Week 2: Rapid Prototyping and Testing

Armed with these insights, the design lead creates three prototype variations testing different approaches to accelerating time-to-value and increasing activation completion:

Prototype A: Simplified activation that removes non-essential steps, uses smart defaults, and defers optional configuration until after users experience core value. Time-to-complete-activation drops from estimated 45 minutes to 8 minutes.

Prototype B: Progressive activation that gets users to a working state in under 2 minutes with minimum setup, then progressively adds capabilities as they use the product. Users reach their aha moment before completing full activation.

Prototype C: Guided activation with contextual help, example templates, and hand-holding through each step. Still takes 45 minutes but has higher completion rates because users understand why each step matters.

The team tests all three prototypes with 25 trial users (current active trials who agree to test prototypes in exchange for extended trial periods). Results are clear: Prototype B (progressive activation) tests highest. Users reach their aha moment in an average of 3.2 hours (versus 48 hours in current experience). 78% of users complete the simplified initial activation (versus 40% completing current activation). Users express significantly higher likelihood to convert after experiencing the prototype.

Week 2: Cross-Functional Workshop to Define Key Results

The product trio synthesizes interview insights and prototype test results, then facilitates a cross-functional workshop with customer success (who support trial users), sales (who sell to enterprise customers), and marketing (who drive trial signups).

The PM frames the workshop: “Based on discovery, we’ve validated that time-to-first-value and activation completion are the primary drivers of trial-to-paid conversion. Users who experience value within 48 hours convert at 3x the rate of users who take longer. Users who complete activation convert at 15x the rate of users who don’t. Our prototype testing validated that progressive activation can reduce time-to-value from 48 hours to under 4 hours while increasing activation completion from 40% to 70%. Now we need to define specific key results that we’ll commit to delivering.”

The workshop produces three key result candidates:

- “Reduce time-to-first-value from 48 hours to 4 hours, measured via analytics tracking time from signup to first successful core workflow completion”

- “Increase activation completion rate from 40% to 70%, measured via analytics tracking users who complete simplified initial activation”

- “Increase trial-to-paid conversion from 15% to 25%, measured via conversion rate of trial signups to paid subscriptions”

The team debates whether Key Result #3 (the conversion rate increase) is truly a key result or just the objective restated. The PM facilitates the discussion: “The objective is increasing conversion to 25%. The key results are the specific outcomes we believe will drive that conversion increase. Time-to-value and activation completion are hypotheses about what drives conversion. If we deliver KR #1 and KR #2, we believe conversion reaches 25%. So KR #3 is really just the objective measurement. We should stick with KR #1 and KR #2 as our committed key results.”

The team also calibrates ambition. Based on prototype testing, reducing time-to-value to 4 hours and increasing activation to 70% should drive conversion from current 15% to approximately 28% (conservatively, assuming some gap between prototype testing and production reality). This exceeds the objective (25% conversion), providing buffer for uncertainty.

The workshop concludes with committed key results:

- KR #1: Reduce time-to-first-value from 48 hours to 4 hours

- KR #2: Increase trial activation completion rate from 40% to 70%

Discovery has transformed a broad objective into specific, validated, measurable key results that the team genuinely believes will deliver the outcome.

Week 2: Tagging Key Results for Validation Tracking

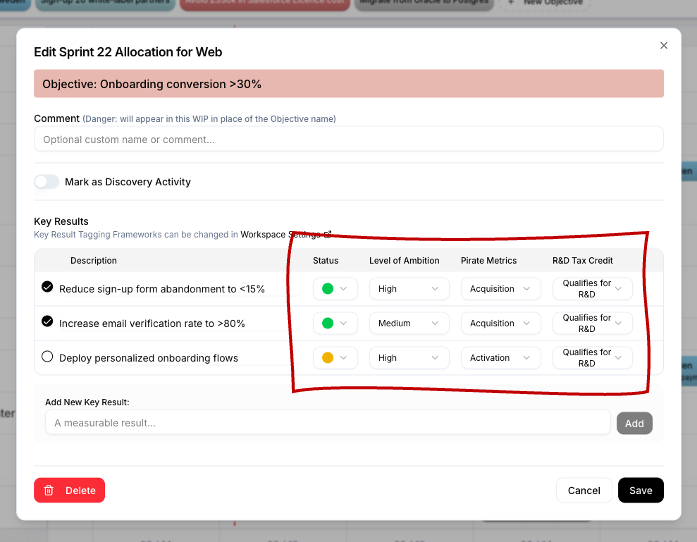

Before transitioning from discovery to delivery, the PM ensures key results are properly tagged using RoadmapOne ’s customisable Key Result tagging frameworks.

Validation Method: Both key results are tagged as “A/B Test” because the team will launch progressive activation to 50% of trial users and measure whether it produces expected improvements versus the control group experiencing current activation.

Confidence Level: The team enters discovery at 30% confidence (the objective seemed achievable but we didn’t know how). After two weeks of customer interviews and prototype testing, confidence increases to 75% (we’ve validated the approach with real users and seen strong positive signals, but haven’t tested at scale yet).

Outcome vs. Output: Both key results are tagged as “Outcome” because they measure user behavior changes (time-to-value, activation completion) rather than delivery outputs (shipping features).

This tagging creates accountability. Teams can track whether discovery actually increased confidence (it should move from 20-30% to 70-80%; if not, discovery failed). They can verify that validation methods are defined before delivery begins (preventing the “how do we measure this?” scramble after features ship). They can ensure key results focus on outcomes rather than outputs (preventing teams from celebrating feature launches without measuring impact).

Key Result tagging frameworks ensure teams define validation methods, track confidence evolution, and focus on outcomes rather than outputs.

Key Result tagging frameworks ensure teams define validation methods, track confidence evolution, and focus on outcomes rather than outputs.

How RoadmapOne Supports the Workflow

RoadmapOne’s design reflects the objective-to-key-result workflow in several specific ways that make the PM’s facilitation role easier.

Objective Allocation Creates the Container

When leadership allocates an objective to a squad, it appears in the objective palette and can be allocated to squad sprints. This allocation is the container that holds subsequent key result definition. The PM allocates the retention objective to Squad A for sprints 5-12: two discovery sprints (5-6) followed by six delivery sprints (7-12).

This allocation makes explicit that Squad A is responsible for delivering the retention objective and has dedicated capacity to do so. It prevents the common problem where objectives float in strategy documents without clear squad ownership or capacity allocation.

Discovery Sprint Allocation Makes Validation Explicit

Marking sprints 5-6 as Discovery allocations signals to everyone (team, stakeholders, cross-functional partners) that these sprints are dedicated to figuring out which key results will move retention. No delivery output expected. Full focus on customer interviews, prototype testing, and assumption validation.

This discovery allocation also accounts for capacity honestly. The roadmap shows two discovery sprints followed by six delivery sprints, not eight sprints of delivery work. Stakeholders see realistic timelines that include the validation work necessary to ensure teams build the right solutions.

Key Result Definition Happens During Discovery

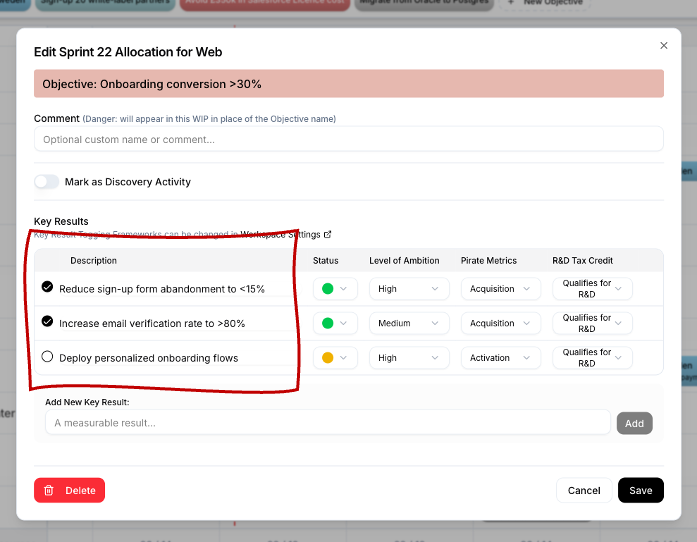

During discovery sprints, the team defines key results through the collaborative process described earlier. In RoadmapOne, key results are created directly on the objective, with tagging to indicate validation method, confidence level, and outcome vs. output classification.

By the end of discovery sprint 6, the retention objective has two key results defined: “Reduce time-to-first-value from 48 hours to 4 hours” and “Increase activation completion from 40% to 70%.”

Delivery Allocations Reference Specific Key Results

When Squad A transitions from discovery (sprints 5-6) to delivery (sprints 7-12), the allocation modal allows selecting which specific key results the squad will work on during those delivery sprints.

This creates traceability from capacity allocation to key result delivery. Stakeholders can see not just that Squad A is working on the retention objective, but specifically that they’re working on the time-to-first-value and activation completion key results that discovery validated.

It also enables splitting delivery work when an objective has multiple key results that different squads can address in parallel. If the retention objective had five key results, Squad A might work on KRs #1 and #2 while Squad B works on KRs #3 and #4, both contributing to the same objective but through different key results.

The allocation modal allows selecting specific key results that the squad will deliver during these sprints, creating clear traceability from capacity allocation to outcome delivery.

The allocation modal allows selecting specific key results that the squad will deliver during these sprints, creating clear traceability from capacity allocation to outcome delivery.

Using Key Result Tagging to Ensure Quality Commitments

RoadmapOne’s Key Result tagging frameworks serve as quality control ensuring teams commit to well-defined, measurable, outcome-focused key results rather than vague activity descriptions.

Validation Method: How Will We Test This?

The Validation Method tag forces teams to define upfront how they’ll validate whether the key result was achieved. Options include A/B testing (comparing new solution to control group), customer interviews (qualitative validation of satisfaction or behavior change), prototype testing (pre-delivery validation with mockups or limited implementations), analytics analysis (measuring behavioral changes via product instrumentation), market research (validating demand or positioning), or user testing (observing users attempting tasks).

When teams can’t identify a clear validation method for a proposed key result, it’s a signal the key result is too vague or immeasurable. “Improve user satisfaction” doesn’t have an obvious validation method because “satisfaction” isn’t operationally defined. “Increase NPS from 42 to 55, measured via quarterly NPS survey” has a clear validation method (NPS survey).

This upfront validation method definition prevents the common scenario where teams ship features, declare victory based on gut feel, then wonder six months later whether the features actually moved business metrics.

Confidence Level: How Certain Are We?

Confidence Level tracking reveals whether discovery is actually working. Teams should enter discovery at low confidence (20-30%—we know the objective matters but don’t know how to achieve it) and exit discovery at high confidence (70-80%—we’ve validated an approach with customers and have strong evidence it will work).

If teams spend two weeks in discovery and confidence doesn’t increase, something’s wrong. Either discovery activities aren’t producing learning (wrong research methods, wrong customers, wrong questions), or the problem is genuinely harder than anticipated and needs more discovery time, or the objective may not be achievable with current constraints.

Confidence tracking also calibrates risk. Committing to delivery at 40% confidence is very different from committing at 75% confidence. Low-confidence key results might warrant smaller initial implementations with more frequent validation checkpoints. High-confidence key results can justify larger delivery investments.

Teams should explicitly discuss confidence levels during the discovery-to-delivery transition: “We’re at 75% confidence that reducing time-to-first-value to 4 hours will increase conversion from 15% to 28%. That’s high enough confidence to commit six delivery sprints. If we were still at 40% confidence, we’d run another discovery sprint first.”

Outcome vs. Output vs. Input: Are We Measuring What Actually Matters?

The Outcome vs. Output vs. Input distinction prevents teams from committing to activity-based key results that don’t measure actual customer or business impact.

Outputs measure features shipped or deliverables completed. “Launch new onboarding flow,” “Ship mobile redesign,” “Complete API v2.” These are work activities, not outcomes. Outputs are necessary for delivery tracking, but they’re not key results because shipping features doesn’t guarantee impact.

Inputs measure effort invested. “Conduct 50 customer interviews,” “Run 20 A/B tests,” “Complete 100 user testing sessions.” These describe discovery or delivery work, not results. You can complete all these inputs without moving any business metric.

Outcomes measure changes in customer behavior or business metrics. “Reduce time-to-first-value from 48 hours to 4 hours,” “Increase activation completion from 40% to 70%,” “Grow trial-to-paid conversion from 15% to 25%.” These measure impact that matters to customers and the business.

The tagging framework forces teams to classify each key result. When teams propose outputs or inputs disguised as key results, the PM redirects: “That’s an output describing what we’ll ship. What outcome do we expect from shipping that? How will customer behavior or business metrics change?”

This outcome focus is critical because it’s entirely possible to ship everything on the roadmap and still miss business objectives if the outputs don’t drive outcomes.

Common Mistakes in Objective-to-Key-Result Breakdown

Even well-intentioned teams make predictable mistakes when breaking down objectives into key results during discovery.

Mistake 1: Skipping Discovery and Jumping to Key Result Assumptions

Teams sometimes take the objective, brainstorm what they think will drive it based on intuition and past experience, declare those brainstorm outputs as key results, and jump immediately to delivery without validating assumptions with customers.

This feels efficient. It’s actually waste disguised as productivity. If the assumptions are wrong (and they often are), teams spend months building solutions that don’t move the objective, discovering only after delivery that they optimized the wrong metrics.

The solution is genuine discovery before commitment. Customer interviews, prototype testing, and assumption validation aren’t overhead—they’re insurance against wasting delivery capacity on wrong solutions.

Mistake 2: Confusing Outputs with Outcomes

Teams propose key results like “Ship improved onboarding flow” or “Launch mobile redesign” or “Complete integration with System X.” These are outputs—things the team will ship—not outcomes measuring customer or business impact.

The solution is the “so what?” question. “We’ll ship improved onboarding. So what? What customer behavior changes? Time-to-first-value decreases. By how much? From 48 hours to 4 hours. That’s the key result.”

Mistake 3: Setting Unambitious Key Results That Won’t Deliver the Objective

Teams set conservative key results to ensure they can hit them, forgetting that hitting key results is only valuable if those key results collectively deliver the objective.

If the objective is increasing retention from 65% to 75%, key results that would move retention from 65% to 67% are insufficient. Even if you achieve them, you fail to deliver the objective.

The solution is calibrating ambition during discovery. “If we achieve all proposed key results, do we believe we reach the objective? If not, either the key results need to be more ambitious, or we need additional key results, or we need to discuss with leadership whether the objective is achievable.”

Mistake 4: Too Many Key Results Without Prioritization

Teams define eight or ten key results thinking comprehensive coverage is better, diluting focus and spreading delivery capacity too thin to make meaningful progress on any single key result.

The solution is prioritizing the vital few. “Which 2-3 key results, if achieved, would deliver 80% of the objective impact? Start with those. If you deliver them successfully and still have capacity, add more.”

Mistake 5: Not Defining Validation Methods Before Delivery

Teams commit to key results but don’t define how they’ll measure success until after features ship, leading to scrambling post-launch trying to instrument analytics or debates about whether the key result was achieved.

The solution is the Validation Method tag forcing upfront definition. “We’ll measure time-to-first-value via analytics event tracking time from signup to first completed core workflow. We’ll instrument these events before shipping the new onboarding flow.”

Conclusion: Where PM Leadership Actually Matters

Product managers spend enormous time on administrative work: grooming backlogs, writing tickets, running ceremonies, updating stakeholders. Much of this work is necessary but doesn’t demonstrate leadership.

Leadership shows up in the objective-to-key-result breakdown during discovery—the collaborative workshop where PMs facilitate teams in transforming broad business objectives into specific, validated, measurable key results that teams genuinely believe will deliver outcomes.

This facilitation requires skills most PMs underutilize: creating psychological safety for experimentation, engaging teams with compelling opportunity framing, guiding the breakdown from vague objectives to specific metrics, synthesizing diverse expertise into coherent hypotheses, and translating discovery insights into roadmap commitments stakeholders can trust.

When PMs lead this process well, teams don’t just execute—they engage. They understand why the work matters. They take ownership of outcomes rather than just shipping outputs. They bring creative problem-solving to challenges rather than minimum-viable compliance with requirements.

Discovery isn’t overhead that slows delivery. It’s the strategic investment that ensures delivery capacity focuses on key results that actually move business objectives. And the PM’s facilitation of that discovery process—especially the objective-to-key-result breakdown—is where product management leadership genuinely matters.

References and Further Reading

- Product Discovery in Roadmaps - Comprehensive guide to making discovery visible and measurable

- Time-Boxed Discovery - How to allocate focused discovery capacity to key result definition

- Key Result Tagging Frameworks - Deep dive into validation methods, confidence tracking, and outcome vs. output distinction

- Objective Tagging Frameworks - Strategic categorization of objectives before breaking them into key results

- Marty Cagan, EMPOWERED: Ordinary People, Extraordinary Products - The SVPG Product Model of leadership allocating objectives while teams define solutions

- Teresa Torres, Continuous Discovery Habits - Practical techniques for collaborative discovery workshops